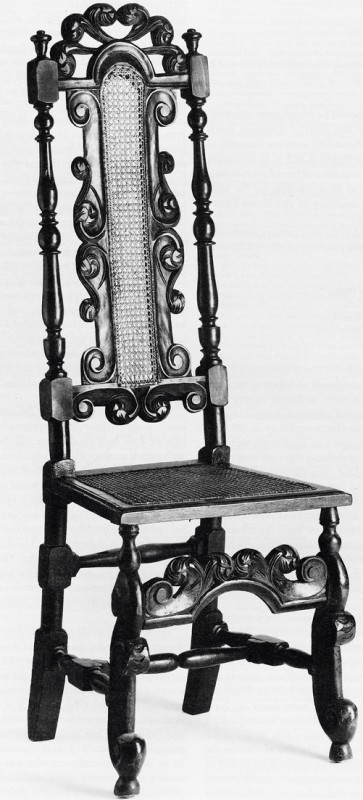

Side chair illustrated on page 252,cat. 52, in Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730: An Interpretive Catalogue (NewYork: W.W. Norton for the Winterthur Museum, 1988). The wood of this chair iscataloged as “American beech.” Species of beechcannot be separated microscopically.

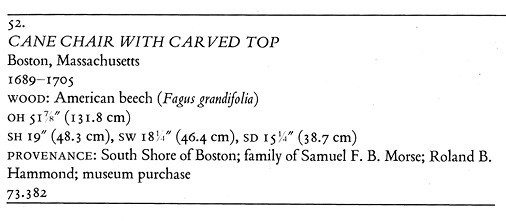

Heading of the catalog entry for the side chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Northern White-Cedar (after Little, Jr.) Elbert L. Little, Jr., Atlas of United States Trees, vol. 1, Conifers and Important Hardwoods, U.S. Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication 1146 (Washington, D.C., 1971), 9 pp., 200 maps.

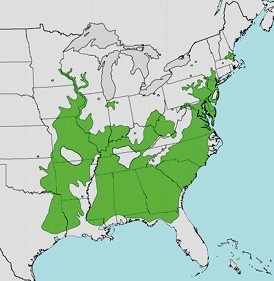

Current Range for River Birch (Betula nigra) Elbert L. Little, Jr.,Atlas of United States Trees,vol. 1, Conifers and Important Hardwoods, U.S.Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication 1146 (Washington, D.C., 1971), 9 pp., 200 maps.

Current distribution of Tulip Poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera). Elbert L. Little, Jr., Atlas of United States Trees, vol. 1, Conifers and Important Hardwoods, U.S. Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication 1146 (Washington, D.C., 1971), 9 pp., 200 maps.

BENNO M FORMAN’S American Seating Furniture 1630–1730—an “interpretive catalogue” of the Winterthur Museum’s collection of chairs, stools, couches, and other forms—is one of the more frequently cited sources in books and articles on that subject. When his work was published in 1988, the author of this article was employed as Wood Researcher at Winterthur and was credited with making “minor corrections to the chapter on woods.” Those corrections were neither minor nor ambiguous, and the author was not made privy to the final draft of that chapter nor to the wood identifications in the catalog entries. Because incorrect and misleading wood identifications made in Forman’s book continue to be repeated by furniture scholars and academics (fig. 1), this article will provide corrections and discuss the value of scientific evidence over unfounded opinions, conclusions, and problematic methodologies.[1]

Author’s Credentials

Corrections to Catalog Entries and Illustrations by Wood

Background: The wood identifications for American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 were done by Gordon Saltar and are identified by being in italics (fig. 2). With the exception of black walnut, none of the species separations made by Saltar can be done microscopically.

Nomenclature: The abbreviation for single species is sp. The abbreviation for species in the plural is spp.

SOFTWOODS

White Pine (Pinus strobus) should read White Pine Group (Pinus sp.).

Figures 33, 170.

Pages 150–19, 182-38, 185-40, 192–44.

HARDWOODS

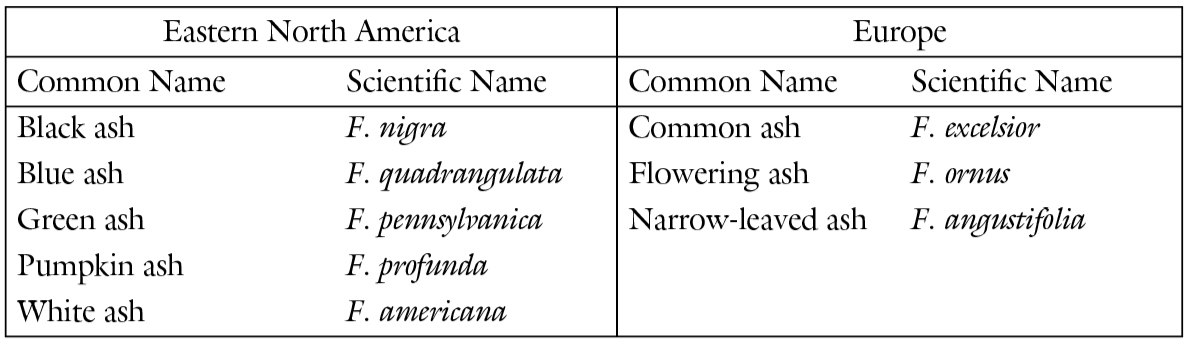

American Ash – Black Ash – Red Ash should read Ash (Fraxinus sp.).

Figures 30, 33, 46, 52, 89.

Pages 93-2, 96-3, 98-4, 101-5, 103-6, 105-7, 108-9,118-12,124-15, 185-40, 317- 67.

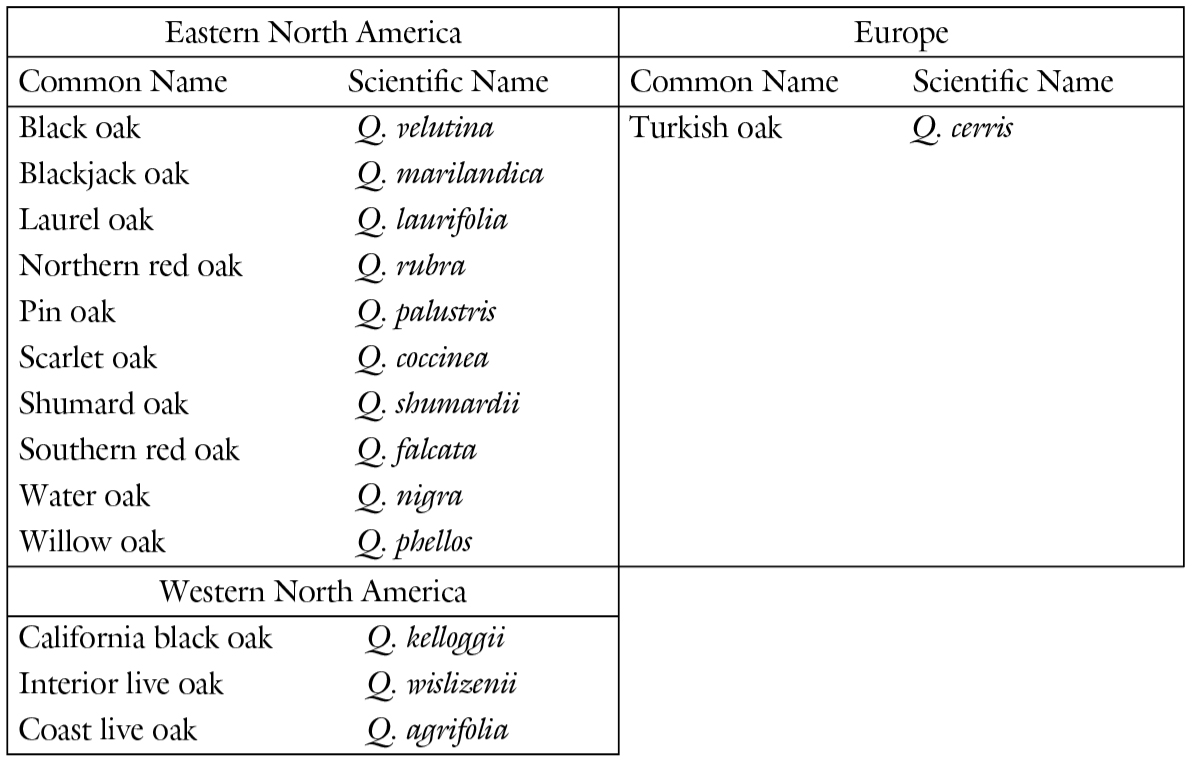

Red Oak (Quercus rubra) should read Red Oak Group (Quercus sp.).

Figure 111.

Pages 148-18, 152-20, 180-35, 180-36, 214-45, 216-46, 308-64, 311-65, 314-66, 320-69, 320-70, 325-71, 333-75, 335-76, 363-87.

Post Oak (Quercus stellata) should read White Oak Group (Quercus sp.).

Page 182-37.

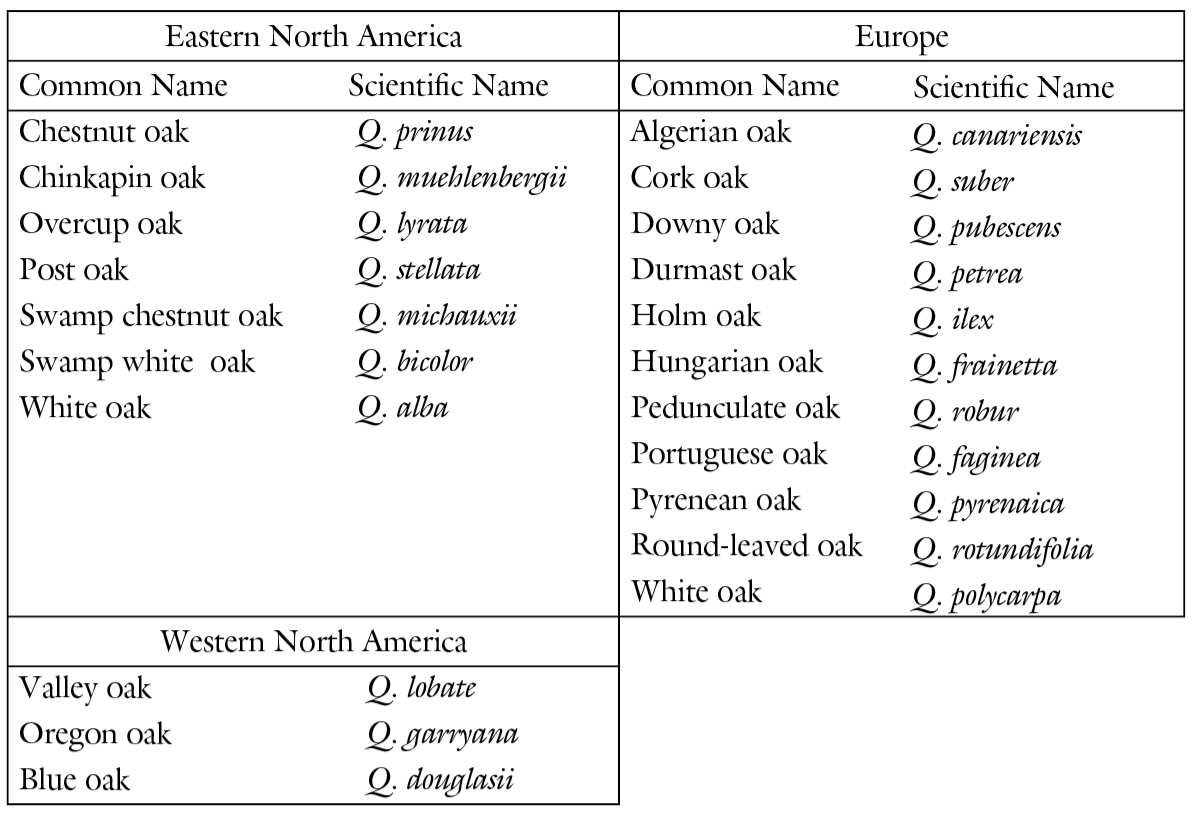

White Oak (Quercus alba) should read White Oak Group (Quercus sp.).

Figure 89.

Pages 105-7, 114-11, 122-14, 150-19, 180-36, 190-43, 220-48, 338-77, 340-79.

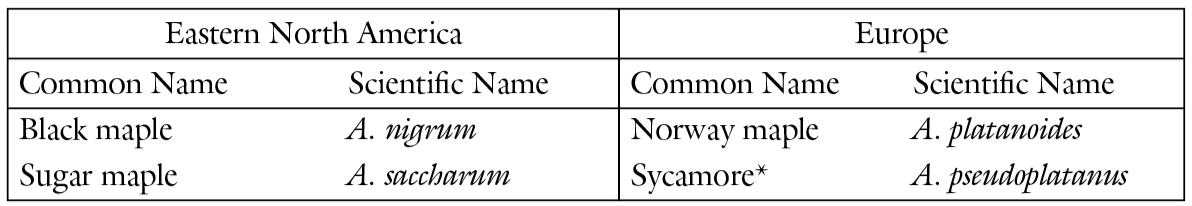

European Field Maple (Acer campestre) should read Soft Maple Group (Acer sp.).

Page 120-13.

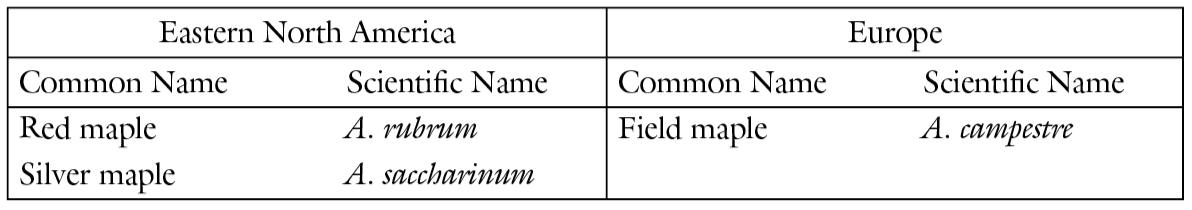

Red Maple (Acer rubrum) should read Soft Maple Group (Acer sp.).

Pages 124-16, 241-45, 216-46, 304-61, 304-62, 306-63, 344-80.

American Silver or Red Maple (Acer saccharinum or Acer rubrum) should read Soft Maple Group (Acer sp.).

Pages 182-38, 325-71, 338-77.

American (Striped) Maple (Acer pennsylvanicum [sic]) should read Soft Maple Group (Acer sp.) [pensylvaticum is misspelled].

Figure 158.

Pages 268-56, 279-60, 311-65, 331-74.

Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) . . . a Maple of the Soft Group should read Hard Maple Group (Acer sp.).

Pages 226-50, 308-64, 335-76.

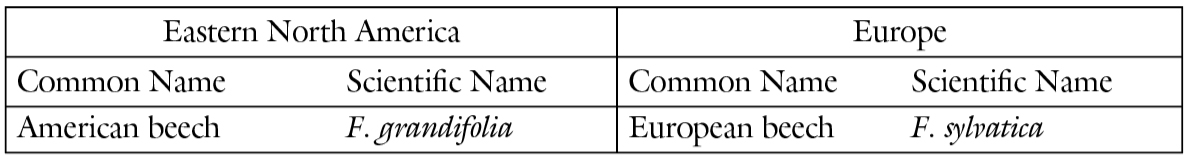

American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) should read Beech (Fagus sp.).

Figures 126, 142.

Pages 251-52, 254-53, 268-55, 328-73.

European Beech (Fagus sylvatica) should read Beech (Fagus sp.).

Figures 99, 116, 126, 163, 173.

Pages 278-59, 279-60.

Ohio Buckeye (Aesculus glabra) should read Horse Chestnut (Aesculus sp.).

Page 96-3.

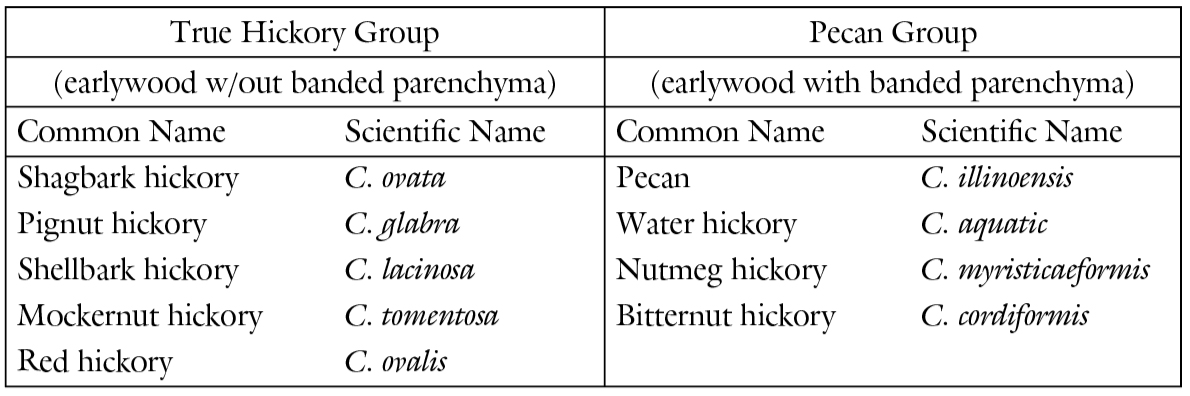

Hickory (genus Carya) should read either True Hickory Group or Pecan Hickory Group (Carya sp.).

Pages 105-7, 112-10, 120-13, 128-17.

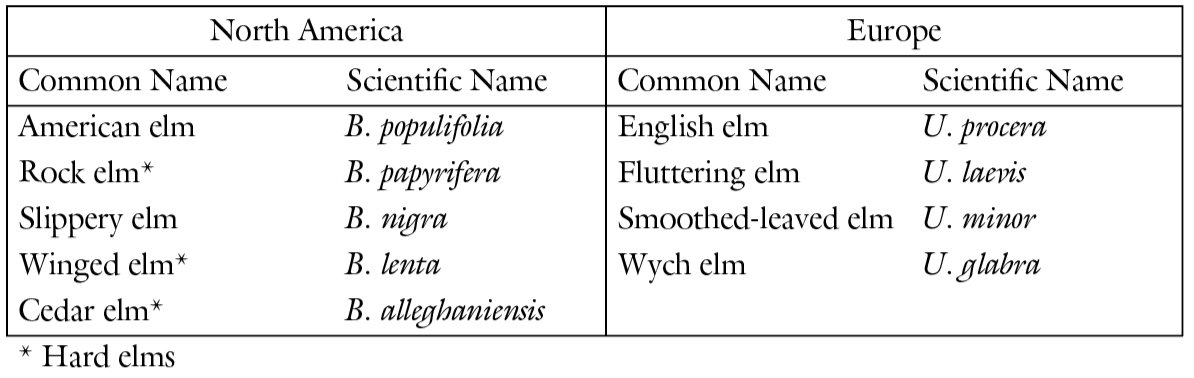

American Elm (Ulmus fulva) or White Elm (Ulmus americana) should read Elm (Ulmus sp.) [Ulmus fulva is an archaic species epithet designation for Slippery Elm (Ulmus rubra)].

Pages 108-9, 340-78.

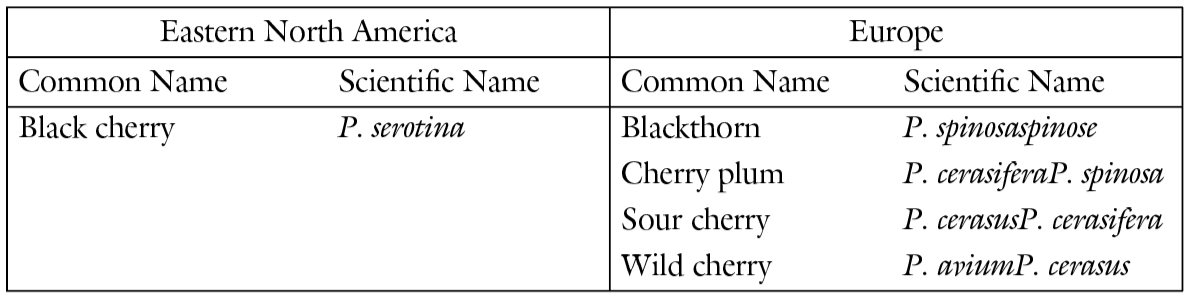

American Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) should read Cherry (Prunus sp.).

Pages 114-11, 118-12.

Fig. 3 The image on the right is labelled “transverse plane.” This is clearly the tangential plane.

Corrections to Chapter 2 with Comments on Wood Identification

PAGE 23:

In the second full paragraph, Forman makes several erroneous statements.:(1) walnut from Salem, Massachusetts, looks the same as walnut from Norfolk, Virginia, or any other place within its growth range; (2) wood from a tree growing on the dry top of a hill will look the same as the same species growing beside a stream at the bottom of the hill; (3) the absence or presence of minerals in the soil does not impart different colors in the same species. In the third full paragraph, Forman states that “Microanalysis is practiced by the professional botanist who is a microanatomist.” Microanatomist is a poor term and too general—it should be a plant anatomist, with additional training in wood identification.

PAGE 24:

Softwoods are conifers and not their “close relatives.” Forman may have been referring to gymnosperms, which include conifers. The “close relatives” of conifers do not produce wood. In figure 5, the wood wedge drawn by Robert Blair St. George and Wade Lawrence has a blatant error. The regions of each growth ring (D) use archaic terms: spring growth should be earlywood (D1) and summer growth should be latewood (D2). Even worse, the drawing has the earlywood produced last in the ring and latewood produced first, which is backwards. In the drawing to the right, the cambium (B) points to the bark (C). At the bottom of the first full paragraph, Forman states that red oak (Quercus rubra) is native only to North America. While this is true, there is a Turkish oak (Quercus cerris) native to Europe that looks exactly like Quercus rubra. Also in this paragraph, Forman describes early growth as composed almost entirely of pith and bark. This is not true; it has some pith but is composed mostly of primary xylem (vessels/pores) with primary phloem (inner bark) and bark. The cambium develops between the primary xylem and primary phloem. This is basic undergraduate botany. In addition, secondary phloem does have anatomical features useful in identification and is not insusceptible. There is also an error in figure 6. Tyloses are not resinous, but are cellulosic extensions of adjacent parenchyma cells. Also, the presence of tyloses in the separation of red and white oak groups is not useful because the sapwood of white oaks is devoid of tyloses, and some species of red oaks have tyloses.[2]

PAGE 25 AND FIG. 5, OAKS SECTION:

In describing rays in oaks, the word “gigantic” should be replaced with “wide” and “fine” should be replaced with “narrow” (or, better, with “uniseriate”). In the fifth full paragraph, tylosis should be replaced with tyloses (the plural form); and tyloses do not dry out, as they are neither liquid nor resinous.

PAGE 28, CONIFERS SECTION:

Thuja occidentalis is not a pine, and it is called northern white-cedar, not to be confused with Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides). Also, the yellow pine that grows in the Connecticut River Valley is pitch pine (Pinus rigida). In the fourth full paragraph, firs (Abies spp.) can sometimes be separated by continent.[3]

PAGE 29, TULIPWOOD SECTION:

First, tulipwood is a species of rosewood (Dalbergia frutescens [Vell.] Britton). Second, it is unlikely that tulip poplar was cultivated anywhere, and it grows naturally in southern Massachusetts (see map at the end of this article).

PAGE 29, MAPLES SECTION:

Species within each group (Hard Maple and Soft Maple Groups) look exactly alike microscopically. Acer pseudoplatanus should be Hard Maple Group. Acer saccharum cannot be distinguished from other species in the Hard Maple Group. The same goes for Acer campestre and the Soft Maple Group. Again, with reference to Gordon Saltar, no species separations are possible. Striped maple (Acer pensylvaticum) should not appear here, because it is a very small understory tree and was not used for anything but small items, like inlays or veneers (see Appendix A).

PAGE 30, BEECH SECTION:

Species of beech cannot be separated microscopically, and Saltar’s “test” was fallacious. His anatomical features for separating beech species were the presence of crystals, ray height/width, and the presence of “tandem” rays. According to Saltar, American beech has “crystals minute of the rays,” tandem rays, and “short rays,” whereas English beech has “long (tall) rays” and “visible small (narrow) rays.” He describes these as “reliable though elusive factors.” Crystals exist in both species but are rare. The term “tandem rays” was apparently invented by Saltar, as the author has never heard of them or encountered that term in scientific literature. The feature Saltar refers to is artefactua, and is a single wide ray bisected by fibers that appears to be two rays. More importantly, Saltar does not use the presence of crystals in beech as a positive character. That is, its presence (to him) indicates American origin, while its absence (to him) indicates English/European origin. This is faulty logic, as crystals (and other features in wood identification) are correctly treated as positive characters, especially when they are scarce. They only can be used in a positive sense, while their absence indicates that the unknown sample could be either species/species groups. This applies to crystals in spruce (Picea spp.) and fir (Abies spp.), and to storied rays and specific gravity in the True Mahogany Group (Swietenia spp.).[4]

PAGE 30-31, WALNUT SECTION:

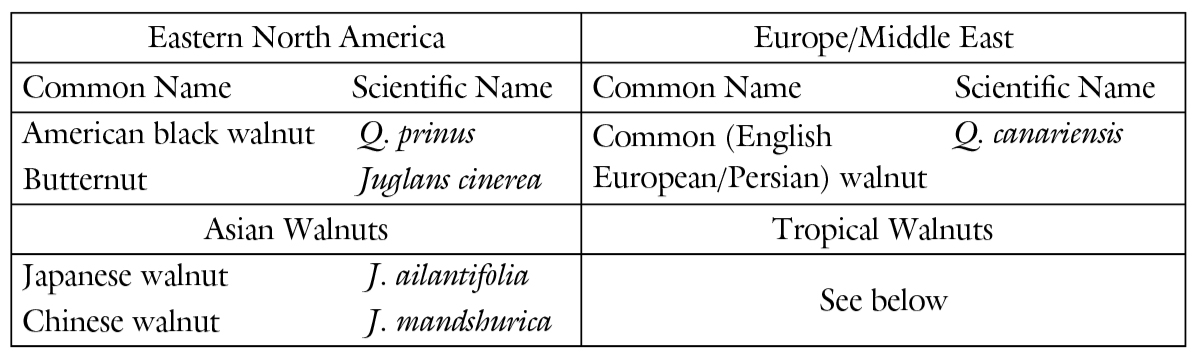

The reference to Juglans regia in the third paragraph is incorrect. Juglans regia is not native to England or Europe, but rather to the Balkans and from Iraq eastward to the Himalayas and southwestern China; its proper common name is Persian walnut. The characterization of American walnut on page 31 should read “American walnut exhibits an irregular thickening of the vessel walls (called gashes) and short chains of calcium oxalate crystals in the axial parenchyma.”

PAGE 32, ASH SECTION:

All species within the genus Fraxinus (ash) look exactly alike microscopically.

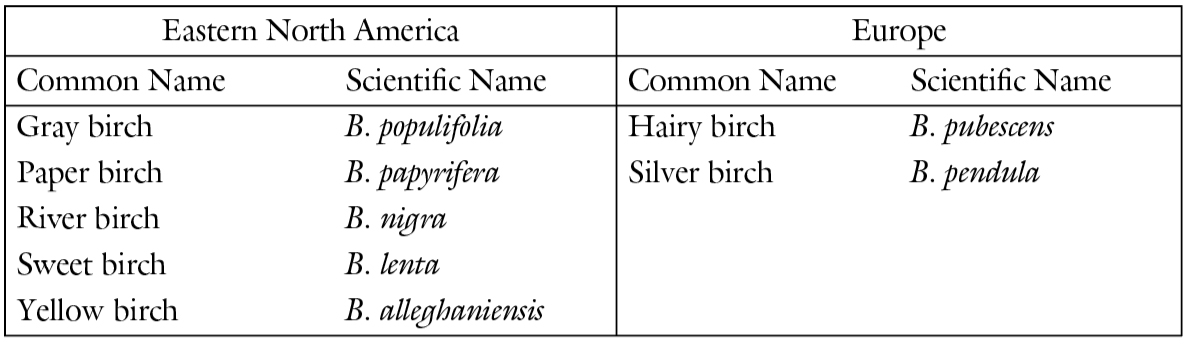

PAGE 33, BIRCH SECTION:

Birch is not always a cold-loving tree. The river birch (Betula nigra) grows in the southern United States to Florida (see Appendix A). Species separations are not possible microscopically.

PAGE 37, NOTES SECTION:

The editor’s note for number 34, stating that “Saltar’s tests for American Beech have been confirmed by Her Majesty’s Forest Products Laboratory at Prince’s Risborough England but they have not been published by Saltar,” is patently false. The author has a copy of Saltar’s explanation of his methodology, and it would never have been published by a peer-reviewed journal. The statement that “research is currently being undertaken to verify Saltar’s techniques” is also false, as the author was the Wood Researcher at Winterthur at the time and expressly informed the editors that species separations of beech could not be made microscopically.[5]

Other Questionable Identifications by Gordon Saltar and Others

Gordon Saltar’s “identifications” in other publications should be questioned. A web search found six:

There are also dubious species assignments made by J. Thomas Quirk (deceased). The author worked with Quirk at the Forest Products Lab. He was not a wood anatomist, but a mechanical engineer transferred to the wood anatomy section. After retiring from the Forest Products Lab, Quirk started a wood identification business. Like Saltar, he often assigned false American species designations.

Microscopic wood identification is a complex process that initially involves the precise preparation of samples, the recognition of cellular characteristics, and the arrangement of cells within the tissue called wood. Secondarily, these cellular characters are then used in: 1) a dichotomous key; 2) entered onto punch-cards; or, 3) into a multivariate computer array (InsideWood, 2004–onwards, published on the internet, http://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/search). Finally, potential taxa generated are compared to reference samples for a final positive identification.

The establishment of new ways to separate genera in tropical woods or species separations in temperate genera requires thorough scientific data collection and analysis, followed up with submission to peer-reviewed journals such as the IAWA [International Association of Wood Anatomists] Journal.

Data from Bruce Hoadley, Regis Miller, and Scott Kitchener indicate that the presence of fusiform ray extensions on radial resin ducts that are 100 microns tall or more indicate deal (Pinus sylvestris), but those authors’ research is only about 70% accurate. While the basic approach is good, the accuracy rate is poor and the sample size needed is impractical for small samples.[6]

There is also a graduate thesis dealing with species separation of ash (Fraxinus spp.). Not all species were examined, the structure and collection of data were poor, and the sample size needed was impractical and is of no use in wood identification. The author has shared a copy of that thesis with the editor of a peer-reviewed wood anatomy journal for comments. The response was that the thesis was unworthy of publication and had questionable scientific value.

Efforts to separate species microscopically with good science are continuing, but there is a limit to how far things will progress. First, species assignments are based on the plants’ (trees’) floral and foliar (leaf) characteristics and, for the most part, wood anatomy at this level is evolutionarily conservative. Second, there are many genera where the anatomical characters of species overlap—in the rosewoods (Dalbergia spp.), for example— making species separations mostly impossible. One must use other features such as specific gravity or density, heartwood colors and their patterning, and chemical tests (water and ethanol extracts color and their color under long-wave UV fluorescence). These latter features require a large sample of approximately 6 x 4 x 1 inches.

Appendix

Generic Descriptions Alphabetically by Common/Trade Name

NORTHERN WHITE-CEDAR (Thuja L./Cupressaceae) is composed of about six species worldwide and is native to North America (2) and Asia (4). Northern white-cedar (T. occidentalis L.) is found in southeastern Canada and northeastern United States to the Lake States region (fig. 3).

WESTERN RED CEDAR (Thuja plicata) ranges from southeastern Alaska to northwestern California and also in the northern Rocky Mountain region. The heartwood of T. occidentalis is a pale brown with a faint but characteristic cedar odor; the heartwood of T. plicata is reddish or pinkish brown to dull brown with a much stronger and spicy aroma.

WESTERN RED CEDAR (Thuja plicata) and northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis) can sometimes be separated based on their microscopic anatomy (B. Francis Kukachka, “Identification of Coniferous Woods,” Tappi 43 [1960]: 887–896). The word thuja comes from the Greek thuia, an aromatic wood (probably a juniper).

PINE (Pinus spp./Pinaceae) is composed of at least ninety-three species worldwide and can be separated into three groups based on their microanatomy: the Red Pine Group, the White Pine Group, and the Yellow or Hard Pine Group.

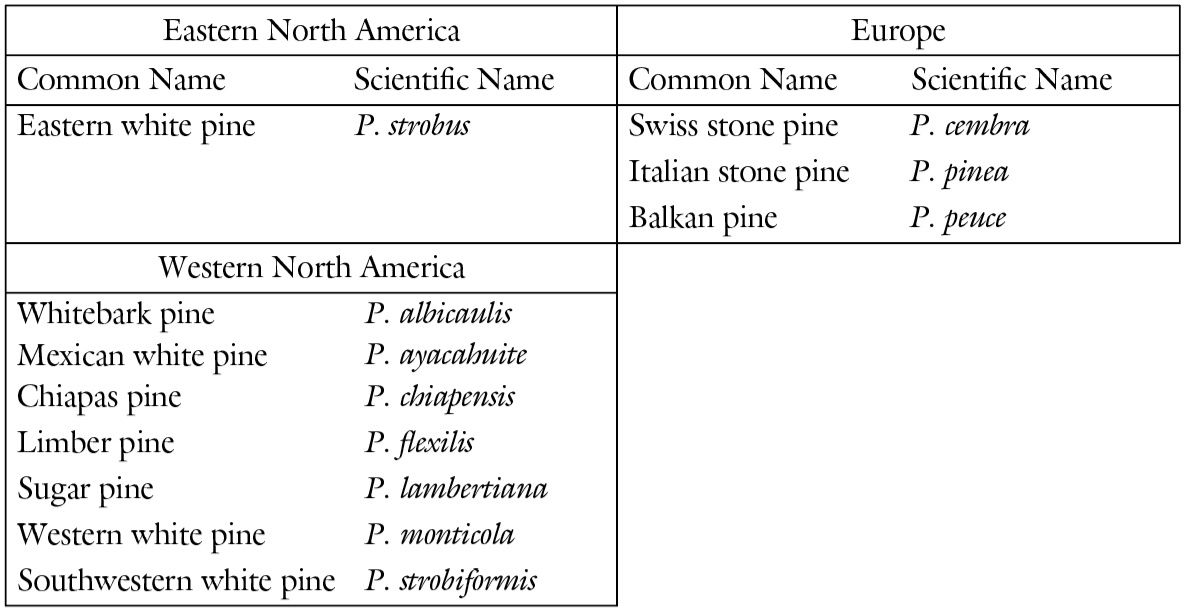

WHITE PINE GROUP contains twenty-one species that grow in Asia (10), Europe (3), Central America (1), and North America (7). All species in this group look alike microscopically. Unless imported as ship masts or crating, the presence of all species other than Pinus strobus would be highly unlikely in American furniture made before the nineteenth century. Pinus strobus is native to the northeastern United States and Canada.

ASH (Fraxinus spp./Oleaceae) is composed of between forty and seventy species, with perhaps twenty-one in Central and North America and fifty in Eurasia. All species look alike microscopically except for Manchurian ash (F. mandshurica)*. The commercial ashes are, to my knowledge:

*Manchurian ash (Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr./Oleaceae) is also known as ash, Asiatic ash, “Chinese Oak,” curly ash, damo, frassino giapponese, frene du Japon, fresno japones, Japanese ash, Japanse es, japansk ask, mandschurische esche, shioji, tamo, ya chidamo, and yachi-damo. It is native to northeastern Asia in northern China, Korea, Japan, and southeastern Russia. It is a medium-sized to large tree reaching heights of 30 meters, with trunk diameters of up to 50 cm.

BEECH (Fagus spp./Fagaceae) contains eight species that grow in Asia (4), Europe (F. sylvatica), and North America (F. grandifolia). All species look alike microscopically.

BIRCH (Betula spp./Betulaceae) is composed of between thirty and fifty species growing in Asia (12), North America (4), and Europe (4). All species look alike microscopically. The common commercial species are to my knowledge:

CHERRY, etc. (Prunus spp./Rosaceae). The genus Prunus contains between 200 and 400 species distributed in most parts of the world, especially the northern temperate regions (North America, Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean). This genus includes cherries, plums, peaches, almonds, and apricots. All species look alike microscopically; however, woods in this genus with a reddish cast (light or dark red) with a light ray fleck are assumed to be cherry. Some samples are more highly figured due to the rays being wider than normal and at a greater concentration than normal. This figure is probably due to the sample coming from an older tree or from parts close to the ground. The tree-size species are, to my knowledge:

Elm (Ulmus spp./Ulmaceae) contains between eighteen and forty-five species native to Asia (11), Europe and the Mediterranean region (6), South and Central America (7), and North America (7). There are species on both sides of the Atlantic that look alike microscopically.

HICKORY (Carya spp./Juglandaceae) is composed of at least sixteen species native to Asia (4), Central America (4), and North America (11) (including southeastern Canada). The European species became extinct during the Ice Age. With a large enough sample, this genus can be split into the True Hickory Group and the Pecan Group based on microanatomy (see M. A. Taras and B. Francis Kukachka, “Separating Pecan and Hickory Lumber,” Forest Products Journal 20, no. 4 [1970]: 58–59).

HORSE CHESTNUT (Aesculus spp./Hippocastanaceae) contains about thirteen species, which grow in the United States (6), Mexico (1), and Eurasia (6). Species cannot be separated based on microanatomy. The name aesculus is a Latin name of a European oak or other mast-bearing tree.

MAPLE (Acer spp./Aceraceae) contains between seventy and 120 species with sixteen species in Asia, eight in North America and eleven in the European/ Mediterranean region. The maples can be separated into two groups based on their microscopic anatomy (ray width), the Soft Maple Group and the Hard Maple Group. Species within each group look alike microscopically.

The commercial species (with respect to American vs. English/European) are to my knowledge:

HARD MAPLE GROUP

Acer pseudoplatanus is known as “sycamore”" in England but is not to be confused with the American sycamore, Platanus spp., which carries the common name “plane tree” in England.

Acer pseudoplatanus is known as “sycamore”" in England but is not to be confused with the American sycamore, Platanus spp., which carries the common name “plane tree” in England.

SOFT MAPLE GROUP

Striped Maple (Acer pensylvaticum) is a small deciduous tree growing to 5–10 meters (16–33 ft.) tall, with a trunk up to 20 cm. (8 in.) in diameter. The wood of the species is diffuse-porous, white, and fine grained, and on occasion was used by cabinet makers for inlay material. Botanists who visited North America in the early eighteenth century found that farmers in the American colonies and in Canada fed both dried and green leaves of the species to their cattle during the winter. When the buds began to swell in the spring, they turned their horses and cows into the woods to graze on the young shoots (William J. Gabriel and Russell S. Walters, “Striped Maple,” https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/acer/pensylvanicum.htm).

Common Uses: Veneer, paper (pulpwood), boxes, crates/pallets, musical instruments, turned objects, and other small specialty wood items. Striped maple is so called because of its distinct green-striped bark. It is much smaller than most other maple species, and with trunk diameters measured in inches, rather than feet, it is seldom used for lumber (Eric Meier, The Wood Database, 2008–2020, https://www.wood-database.com/stripedmaple/).

OAK (Quercus spp./Fagaceae) contains between 275 and 500 species and can be separated into three groups based on their microanatomy: the Live or Evergreen Oak Group, the Red Oak Group, and the White Oak Group. Species within each group look alike microscopically. For colonial American objects, Live and Red Oak Groups are indicative of American origin, whereas the White Oak Group could be from either side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Species of the White Oak Group were used in American and English furniture. To my knowledge, species in the Red Oak Group were not commercial timbers in Europe and England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Quercus cerris (Turkish oak), a species in the Red Oak Group, was introduced into England in the late 1730s from the Mediterranean region as an ornamental tree. Its appearance in furniture would be astronomically rare. Based on these assumptions, furniture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries containing wood of the Red Oak Group is most likely American in origin.

RED OAK GROUP (Erythrobalanus)

WHITE OAK GROUP (Leucobalanus)

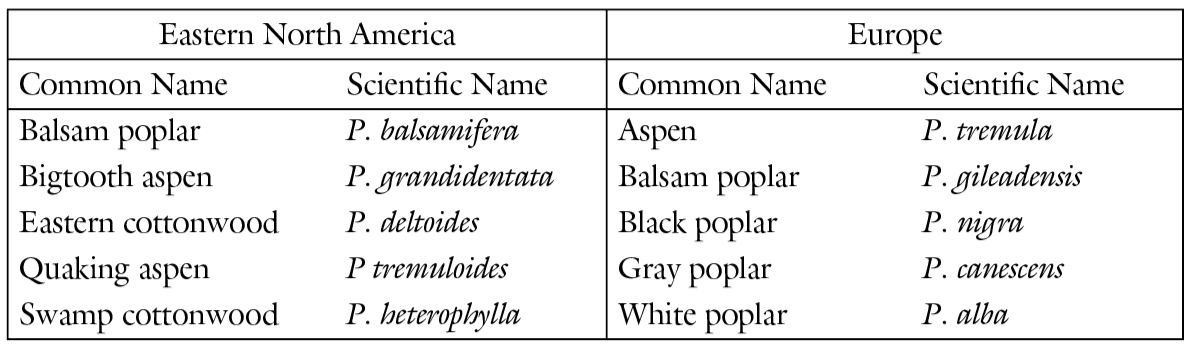

TRUE POPLAR GROUP (Populus spp./Salicaceae) Populus sp. is a genus of thirty-five species that contains poplar, cottonwood, and aspen. Species in this group are native to Eurasia/North Africa (25), Central America (2), and North America (8). All species look alike microscopically.

TULIP POPLAR (Liriodendron spp./Magnoliaceae) contains two species, the yellow poplar/tulip poplar of North America (L. tulipifera) and the Chinese tulip tree (L. chinensis). Both species look alike microscopically.

WALNUT/BUTTERNUT GROUP (Juglans spp. L./Juglandaceae) contains about twenty species (walnuts and butternuts) that grow in South America (6–11), Eurasia (5), and North America (4). If the sample is large enough, tropical walnuts (6–11 spp.), American black walnut (Juglans nigra), common English/European/Persian walnut (Juglans regia), and the butternuts (4 spp.) can be separated from each other based on microanatomy. Microscopic characters needed for a positive Juglans nigra identification are: 1) irregular wall thickenings in latewood vessels (“gashes”); and, 2) calcium oxalate crystals in axial parenchyma cells in short chains of 1–4 (see Regis B. Miller, “Wood Anatomy and Identification of Species of Juglans,” Botanical Gazette 137, no. 4 [1976]: 368–377). I currently have no anatomical information on California walnut (Juglans hindsii).

With regards to color, Juglans nigra and the Tropical Walnuts usually have a dark brown to red-brown colored heartwood. Asian Walnuts and Juglans regia, on the other hand, have a heartwood that is usually a light tan but can range in color to dark brown.

TROPICAL WALNUTS

J. australis Griseb. (J. brasiliensis Dode)—Argentine walnut, Brazilian walnut J. boliviana (C. DC.) Dode—Bolivian walnut, Peruvian walnut

J. hirsuta Manning—Nuevo León walnut

J. jamaicensis C. DC. (J. insularis Griseb.)—West Indies walnut

J. mollis Engelm—Mexican walnut

J. neotropica Diels (J. honorei Dode)—Andean walnut, cedro negro, cedro nogal, nogal, nogal Bogotano

J. olanchana Standl. & L.O. Williams—cedro negro, nogal, walnut

J. peruviana Dode—Peruvian walnut

J. soratensis Manning

J. steyermarkii Manning—Guatemalan walnut

J. venezuelensis Manning—Venezuela walnut

Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730: An Interpretive Catalogue (New York: W. W. Norton for the Winterthur Museum, 1988).

Harry A. Alden and Alex C. Wiedenhoeft, “Qualified Determination of Provenance of Wood of the Firs (Abies spp. Mill.) Using Microscopic Features of Rays: An Aid to Conservators, Curators and Art Historians” (poster presentation, 26th American Institute of Conservation Annual Meeting, Arlington, Va., June 1–7, 1998).

Author’s personal observation at the USDA, Forest Service, Forest Products Research Laboratory, Center for Wood Anatomy Research. I examined all of the Quercus specimens in the MADw and SJRw collections with a hand lens. These are the two collections making up the largest research wood collection in the world. I found several species of the Red Oak Group with tyloses. Also, species in the White Oak Group with sapwood showed no tyloses, as they are features of the heartwood.

Memo from Gordon Saltar, 1978, Joseph Downs Collection and the Winterthur Archives, Winterthur, Del.

Ibid.

R. Bruce Hoadley, Regis B. Miller, and Scott Z. Kitchener. “Distinguishing Pinus resinosa Ait. and Pinus sylvestris L. on the Basis of Fusiform Ray Characteristics,” IAWA Bulletin 11, no. 2 (1990): 126.